http://www.bbc.co.uk/nature/adaptations

Adaptations help organisms survive in their ecological niche or habitat; adaptations can be anatomical, behavioural or physiological.

Anatomical adaptations are physical features such as an animals shape. Behavioural adaptations can be inherited or learnt and include tool use, language and swarming behaviour. Physiological adaptations include the ability to make venom; but also more general functions such as temperature regulation.

Adapted to extremes

Adaptation to extremes encompasses all the special behaviours and physiologies that living things need to withstand the planet’s harshest conditions and environments. Whether it’s a lack of oxygen at altitude, the searing heat of deserts or the bitter cold of the polar regions, plants, animals and other organisms have evolved a multitude of coping strategies

Chemical tolerant

Chemical tolerant describes organisms which can tolerate high concentrations of substances which would be toxic or corrosive to other life. For instance plants that can live in the acidic and low oxygen conditions of peat bogs, flamingos that can tolerate the alkaline waters of soda lakes and brine flies which can live and breed on salt flats.

Cold tolerant

Cold tolerant organisms have evolved various methods for coping with very low temperatures. Some animals hibernate, take shelter, or even migrate to warmer areas. Others, such as Antarctic seals, have warm fur and a thick layer of blubber for insulation. Arctic plants tend to be small and grow low to the ground and can be coated with hair and wax to avoid wind chill. Some insects, amphibians and microbes can even withstand being frozen solid.

Behavioural pattern

Behavioural pattern describes an animal’s dominant way of life. Arboreal animals, for example, live in trees and nocturnal animals are active at night.

Cave dweller

Cave dwelling, or troglophilic, animals spend their whole lives in cave systems. Living in perpetual darkness, many cave species have lost the sight that their evolutionary ancestors had and become blind. Vestigial eyes can often be seen. They’re also usually pale in colour as they don’t need to produce skin pigment as camouflage or protection from the sun.

Sessile

Sessile describes animals that don’t move around, such as barnacles and corals. There may be mobile phases in the life cycle, often in the larval stage, where organisms might actively swim or merely drift about, but they will eventually fix themselves in place and remain there for the rest of their lives. Because sessile animals can’t go off in search of food, this is only a practical lifestyle if you live in water, where the currents or tides will carry food particles to you.

Swarming

Swarming happens when animals gather or travel together in large numbers. Its most familiar examples are in insects, such as locusts and midges, flocking birds and shoaling fish. Some animals swarm as a defence against predation, others, such as locusts and bees, only form swarms in specific circumstances. Swarming can be carried out by the smallest and simplest micro-organisms, such as bacteria, and even by humans.

Communication and senses

Communication and senses are how an organism perceives the world – for instance through scent or sight – and how it sends messages or warnings to others.

Tactile sense

Tactile sense includes the obvious sense of contact with another object, but also incorporates a bird’s ability to sense air flow over its wings and a fish’s sensitivity to water movements. Some creatures, such as the yapok and the star-nosed mole, have a highly sensitive sense of touch through specialised organs that they use in situations where eyes are of no use.

Visual communication

Visual communication transmits information to others through shape, colour and movement or body language. Animals can both send and decode visual messages, using colour and behavioural displays for messages as varied as threat, invitations to mate and identification of what species they are. Though plants can’t themselves see, they use visual cues such as colour to attract animals to their flowers and fruits. Visual perception differs radically among various groups of animals, from the ability to see in low light, to detection of the slightest movement.

Life cycle

Life cycle describes all the different stages through which an animal, plant or other organism passes from conception, through adulthood to death. Encompassed here are not only the major physiological stages of growth and development, but also temporary occurrences such as moulting and experiential phases such as courtship and parenthood.

Metamorphosis

Metamorphosis is when a species changes body shape and structure at a particular point in its life cycle, such as when a tadpole turns into a frog. Sometimes, in locusts for example, the juvenile form is quite similar to the adult one. In others, they are radically different, and unrecognisable as the same species. The different forms may even entail a completely new lifestyle or habitat, such as when a ground-bound, leaf-eating caterpillar turns into a long distance flying, nectar-eating butterfly.

Moulting

Moulting is all about renewing your skin, fur or feathers, and occurs in animals for a number of reasons. Some creatures, such as snakes and insects, need to shed their skins in order to grow. Birds moult their feathers at least annually to replace damaged ones, and some species also take the opportunity to change into breeding colours or to turn white in winter for camouflage. Mammals may shed their fur for a thicker winter or thinner summer coat, and again some types may change fur colour with the seasons.

Paternal care

Paternal care is where the father of the offspring provides most or all of the effort needed to protect, feed or raise the young until they become independent. The most well-known example of paternal care is in seahorses, where the male broods the eggs in a pouch until they are ready to hatch. Primary paternal care is most common in egg-laying species and almost unheard of in mammals.

Locomotion

Locomotion is how an animal gets around – for instance by swimming, flying or climbing.

Adapted to swimming

Adaptations for swimming enables animals to move around in water. Animals that can swim proficiently (natatorial) fall into three categories. Those that evolved in water (for instance sharks and jellyfish), those that had land living ancestors but have returned to an aquatic life (dolphins and manatees) and those that split their time between water and land (penguins, crocodiles) and need to move around efficiently in both mediums. Animals that simply go for a swim now and then – say to cross a river – are not specifically adapted to swimming, though this behaviour may be of interest.

Morphology

Morphology is anything to do with what a plant or animal looks like – its size, shape, colour or structure.

Camouflage

Camouflage is the art of not being seen, practised by predators, prey and plants. Colour might help an organism blend in with their environment – even when the organism itself cannot see in colour. Body shapes can make them appear to be some other object common in the same surroundings. Patterns might sometimes make an animal more noticeable, but they can also help disguise outline. The tiger’s stripes and the giraffe’s patches make them almost impossible to detect in dappled light.

Neoteny

Neoteny refers to animals that retains juvenile features even when they become adults. The most well-known example is the axolotl, a type of salamander that remains tadpole-like all its life, never losing its gills and never leaving the water to live on land. Neoteny is an important feature in evolution: human beings are neotenous primates and insects might be descended from a neotenous millipede-like ancestor.

Polymorphism

Polymorphism means ‘many forms’ and can be exhibited in a variety of ways. A truly polymorphic species has individuals of notably different appearance living in the same area. Army ants, which have workers of different sizes in the same nest, are therefore polymorphic as are adders which can have a zig-zag pattern on their skin or be uniform black in colour. If the difference is between males and females of a species, as with peacocks and peahens, it’s sexual dimorphism rather than polymorphism.

Predation strategy

Predation is catching and killing an animal in order to eat it and different species have evolved a range of strategies for doing this efficiently. The most frequently used methods are variations on chasing and capturing if the predator is a fast runner, ambushing to conserve energy, or using a trapping mechanism such as a spider’s web.

Ambush predator

Ambushing prey is a tactic employed by a whole host of animals, from trapdoor spiders lurking in their burrows, to a cat stalking a mouse. If ambushers chase their prey at all, they do so for only a short time, as most of them are not capable of a prolonged pursuit. Instead they use cover so they can surprise unsuspecting prey.

Predator

Predators are creatures that catch and kill other animals for food. All sorts of techniques are employed by different animals to maximise their chance of catching prey, and to balance the energy expended in catching prey with the energy gained in eating it. Some execute long chases, outrunning their prey, others ambush or hunt in groups. Some construct elaborate traps and many have mechanisms for stunning or poisoning their victims.

Reproductive strategy

Reproduction covers all the tactics and behaviours involved in obtaining a mate, conceiving the next generation and successfully raising them. It includes everything from plants being pollinated, to stags fighting over hinds, to lionesses babysitting their sisters’ cubs.

Hermaphroditic

Hermaphrodites have both male and female sex organs, either throughout their lives (homgamy) or that develop and mature at different points in their life cycle (dichogamy). Most dichogamous species, including many flowers and fish, change sex only once in their development. These organism still need another individual at the opposite stage for fertilisation. Homgamous species may be capable of self-fertilisation, but generally two individuals exchange sex cells and both are fertilised.

Monogamous

Monogamous animals partner up with a single mate, sometimes for the duration of a breeding season and less commonly over multiple seasons and years. Monogamy has particular advantages, and is often the chosen strategy where young are more vulnerable and require both parents for protection and feeding. In serial monogamy, having different partners each season helps maintain genetic diversity.

Ovoviviparous

Ovoviviparous animals produce eggs inside their body, but then give birth to live young. The eggs hatch out inside the mother and the offspring stay within her for a time. She later gives birth to the them. While they are within her, the young are fed on the yolk of the egg, and not directly from the mother’s body. Ovoviviparity is a special type of viviparity. Some fish, amphibians and reptiles reproduce this way, for instance the sand tiger shark.

Polygynous

Polygynous sexual behaviour is the system in which a single male mates with multiple females, but each female mates with only one male. This usually entails fierce competition between the males during the breeding season. Females invest more heavily in their offspring and all the parental duties fall to the mother. They become much more choosy about their mate as a result, while the males attempt to have as many mates as possible in order to leave a maximum number of offspring. However many males fail to win or impress a female and remain unmated their entire lives.

Semelparous

Semelparous organisms reproduce only once in their lives and then die. The most well known ones are Pacific salmon that perish after spawning. Other examples are squid, mayflies and plants which die after setting seed (annuals). The adult diverts resources into producing huge amounts of offspring to ensure sufficient numbers reach maturity without any parental care. This is why bears largely ignore dead salmon after they’ve spawned – all the salmon’s fat has gone into producing sperm and eggs and little nutrional value is left.

Spawning

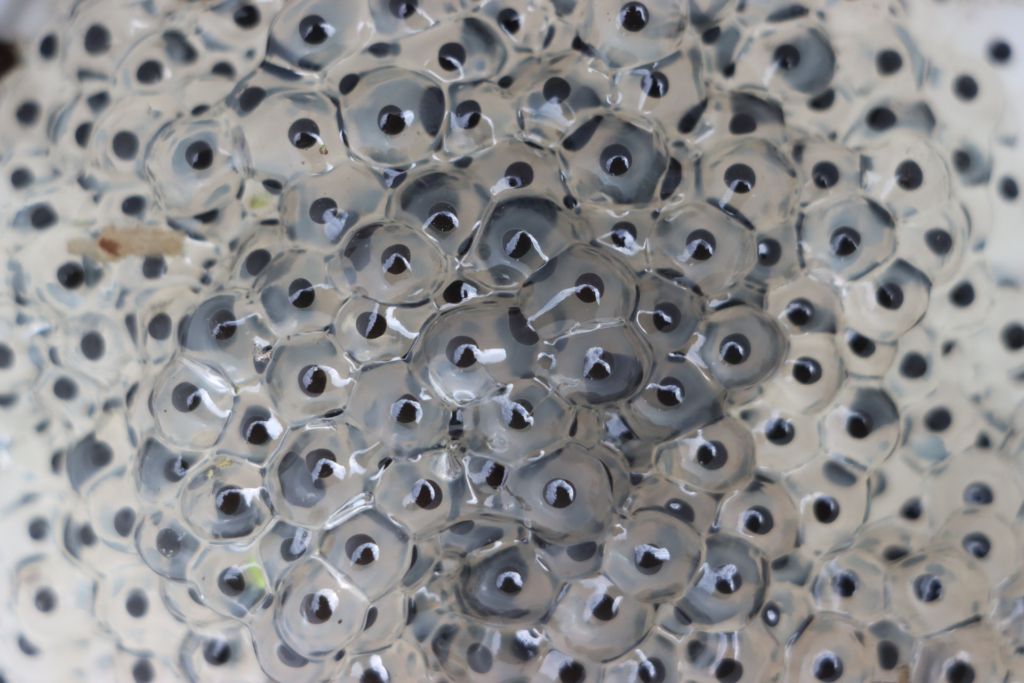

Spawning animals deposit a mass of eggs and sperm in water, where they meet and are fertilised. Even when the male and female animals are in close proximity, such as a male frog grasping the female, the eggs are fertilised outside the female’s body. Some animals, such as coral and many fish, synchronise their spawning so that millions of eggs are released at once in often quite impressive events.

Viviparous

Viviparous animals bear live young that have developed inside the mother’s body. Most familiar to us in mammals, there are a few unexpected ocurrences in animal groups usually associated with egg-laying such as reptiles, amphibians, fish and scorpions. The term can also be applied to some plants, such as certain kinds of succulents and waterlilies, where the seeds germinate while still attached to the parent.

Social behaviour

Social behaviour is all about how an animal interacts with members of its own species. For instance, does it live in a colony or on its own, does it fight to be top of the pecking order, or does it try to keep strangers away from its home?

Colonial

Colonial animals live in large groups in close proximity to one other. Colonies might exist only at specific times of the year such as the nesting season for many seabirds. Others, such as a beehive or a den of meerkats, contain a single social unit,and often last for longer than the lifetime of an individual member.

Eusocial

Eusocial describes species with a very highly developed social structure. Ants and termites are all eusocial, as are some species of bee and wasp and a few very unusual mammals. Eusocial animals live in colonies in a strict caste system. The queen and her consort are the only members of the colony that breed and the majority of offspring become workers and soldiers who gather food, protect the colony and raise the young on the queen’s behalf.

Survival strategy

Survival strategies enable organisms to cope with particular stresses, from temporary environmental changes in the weather to the constant threat of predation. So, for instance, to avoid the cold of winter animals may migrate away or hibernate, while trees may shed their leaves. To avoid predation, plants may be poisonous or covered with defensive spikes and animals may use camouflage or travel in great numbers.

Predation defence

Predation defence comes in many forms: physiological, anatomical and behavioural. Physical defences such as spines and armour are obvious adaptations, but other defences can be more subtle and surprising. Whether it’s avoiding detection through camouflage and mimicry, chemical defence through being poisonous or exuding irritants, it’s all about one thing: avoiding being eaten. Some animals rely on increasing their chances of detecting predators by living in groups and using alarm calls to warn each other of danger.